India-China border dispute (GS Paper 2, International Relation)

Context:

Historical legacy, combined with the expansionist agenda of China, has not only resulted in continuing border dispute between India and China but also lack of clarity on the Line of Actual Control (LAC).

Background:

- The term LAC, which was first coined by former Chinese premier Zhou Enlai in his 1959 letter to Jawaharlal Nehru, was accepted by India as late as 1991, followed by the agreement of Peace and Tranquility signed in 1993.

- The current day LAC is quite close to the Chinese-claimed borders, which is a huge disadvantage to India.

- India has insisted that China must revert to physical locations held as of September 8, 1962, and that it should be held as the basis for delineation of the LAC, while negotiations can continue on final settlement of the border.

What is the real issue surrounding delineation of the LAC?

- The delineation of the LAC has also not been done based on the accepted norms of control as mentioned in the 1993 agreement. This has resulted in the existence of a number of areas of differing perceptions all across the LAC which is the primary cause of conflict.

- Not only this, China has been altering its claim lines multiple times and trying to push them more towards India, thus clearly manifesting its salami slicing on the lines it did in the maritime domain. It has even changed its documented stance and has been looking for justifications for the conflict escalation.

- China should not have developed infrastructure in the Indian-claimed areas. Leave aside this, had it been a good neighbour, it should not have built infrastructure in the areas of differing perception. The infrastructure is being developed at an unprecedented pace by China in these areas. These are potential sovereignty markers which will be a restricting factor for future negotiations.

- While troops of both sides are face-to-face with each other, including the deployment in the depth areas, the discussions so far have failed to prevent the current Chinese incursions along the LAC in eastern Ladakh.

- Not only have higher-level military talks failed to break the deadlock, the political engagements at the level of foreign ministers and defenceministers also have not been able to resolve the current flare-up. The enhanced air activity beyond the specified limits are indirect declarations for future conflict escalation.

India’s claim:

- India and China had Tibet between them. Therefore, the boundary between India and Tibet would have been a relevant border between India and China even after the forceful capture of Tibet by Beijing.

- India claims the length of border as 3,488 kms whereas China claims only 2,000 kms as it excludes Aksai Chin as part of the Indian border, in addition to the marginal differences in some other areas.

Sectoral divison:

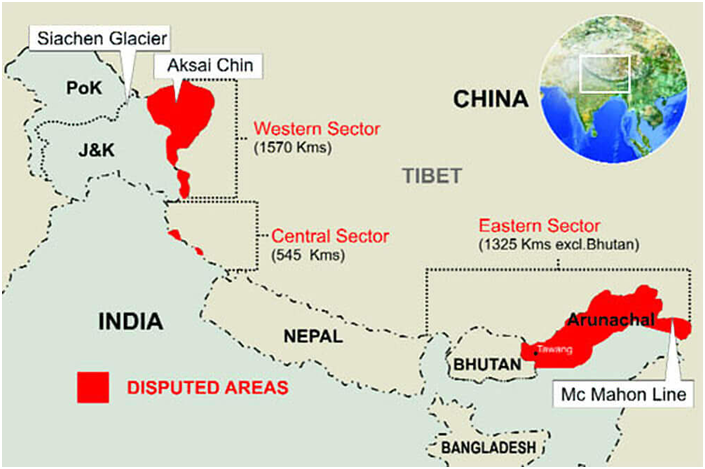

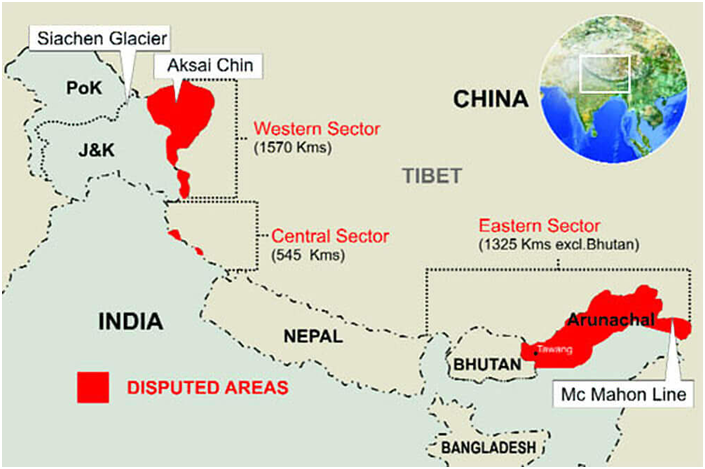

The India-China border can be divided into three areas - western sector, middle sector, and eastern sector.

Western sector:

- This sector comprises the area between Ladakh to Tibet and the Kunlun mountain range and also extends from Wakhan (Afghanistan edge) to the Karakoram Pass, thereafter following the alignment of the Kunlun mountain range.

- The border length of the western sector is 1,597 kms. India's claim is based on the Treaty of 1842 which was signed between the representative of Maharaja Gulab Singh, former ruler of J&K, with Lama Gurusahib of Lhasa and the representative of the Chinese emperor.

- It needs to be understood that China was ruled by the Qing dynasty till 1911 before it was replaced by Chinese nationalists led government, called the Republic of China (ROC) in 1912. In 1949, power shifted to the People's Republic of China (PRC).

- The 1842 treaty line was further modified as the Johnson-Ardagh line of 1897. It is this alignment which is the basis of the Indian-claimed border and was formally stated in 1954.

- Though China was not a signatory of this line (in any case, it was not a treaty), it used this alignment even beyond 1933 in various official and unofficial communications. This was de-facto acceptance of this line which puts the entire Aksai Chin as part of India being a successor state of British India.

- The British were primarily concerned with their own interests and wanted to checkmate the growing Russian influence as part of the Great Game. The British propounded the Kunlun mountain range as the eastern border with Tibet while they drew the Durand Line with Afghanistan as their western border in 1893.

Changing British stance:

- The western sector has been a witness of the changing British stance wherein, in 1899, they drew a fresh line as border alignment, known as the Macartney-McDonald Line that excludes the Aksai Chin. China has been claiming their borders based on this alignment.

- The British changed their stance again in 1905 and 1912 and accepted the Ardagh Line of 1897 as a boundary. But no formal intimation was given to China. However, China used this alignment from 1897 as late as post 1930, which is indicative of its acceptance of this line.

- By all standards, this area is the most challenging task for the border negotiations. The China-Pakistan collusivity, Karakoram highway, CPEC corridor and the renewed infrastructure development with increased settlement of the civil population has further reduced the flexibility of negotiations.

- China Land Border Law, which came into effect on January 1, 2022, has already changed the tenets of territorial disputes to sovereignty disputes.

Middle Sector:

- This comprises the states of Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand. This is the least disputed sector and covers 545 km of Indian borders. Except for the larger claim of China in the Barahoti sector in Uttarakhand, other claims and counterclaims are miniscule.

- These areas have higher chances of both the LAC and the International Border being delineated.

- But the Chinese approach to go for a final boundary settlement in one go has come as a stumbling block as it has been attempting to seek major concessions in the western sector in lieu of acceptance of the McMohan Line in the eastern sector.

- China is also undertaking fast-paced infrastructure development opposite these areas. India also needs to develop credible and quality roads up to the passes besides laterally connecting them.

Eastern Sector:

- The eastern sector conventionally refers to Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh, but both these states have Bhutan separating them. Though Sikkim has a land border of only 220 km and has been witness to both the 1962 as well as 1967 Nathula-Chola conflicts, the situation has normalised a lot after it joined the Indian state on May 16, 1975.

- With ambassadorial relations restored with China in 1976, this border of Sikkim has been relatively peaceful. China finally recognised Sikkim as part of India in 2003 in a reciprocal statement by India to re-emphasise Tibet being part of China.

- Though there are some areas of conflict between India, China and Bhutan, this area also has huge potential for settlement of the border as well as LAC. An understanding with Bhutan will also be essential for the resolution.

Arunachal Pradesh:

- Areas opposite Arunachal Pradesh and others also have huge historical baggage. They relate to the dispatch of a British expeditionary force under Francis Younghusband in 1903-04 which resulted in the Aglo-Tibetan Treaty of 1904. This treaty had indicated unease in China's Qing dynasty, but nothing was done as it had started weakening.

- Direct discourse between the British and Tibetans continued till 1908. In 1911, in the last year of the Qing dynasty, Tibetans revolted and asked for British intervention.

- A tripartite conference was held at Shimla between the representatives of British India (McMohan), Tibet and China. Deliberation commenced in November 1913 and the McMohan Line was drawn and initialed by all the three representatives in the draft document on April 27, 1914. This document was not formally signed by Chinese representatives in the main document.

- The land border, as per this line, covers a length of 1,126 km. This document was finally signed by Britain and Tibet on July 3, 1914.

- The border in Arunachal Pradesh, as per the McMohan Line, has been a part of China's formal offer for border settlement but not by itself. It has been proposed only in lieu of seeking a concession in the Aksai Chin area in Ladakh. The LAC also has a large number of areas of differing perceptions which remain a cause of regular skirmishes or local conflicts.

- China has made large encroachments in this area and a fair number of them during the 1962 war. It has also established Wangdung camp south of Samdurong Chu on the Indian side, which led to a major response by India in 1987. While India has improved its forward positions in a number of areas, Wangdung camp continues to be under Chinese occupation.

Way Forward:

- India-China have historical legacies to their border dispute. A unilateral war launched by China in 1962 and activities thereafter have led to mutual distrust.

- No success has been achieved even after 73 years of the People's Republic of China assuming the current form of government either on LAC alignment or on the border issue.

- The expansionist agenda of China has reached new crescendos with LAC incursions in Ladakh, which is also not getting resolved as Beijing is not agreeing to go back to April-May 2020 positions.

- The stance is similar wherein it did not go back to the September 8, 1962 positions for delineation of LAC. Only an empowered and capable India with a pragmatic approach can resolve the border issue with China.

Indian bureaucrat appointed to inaugural Internet Governance Forum Leadership Panel

(GS Paper 2, International Relation)

Why in news?

- Secretary in the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology Alkesh Kumar Sharma is among 10 eminent persons from around the world appointed by UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres on his inaugural Internet Governance Forum (IGF) Leadership Panel.

What is Internet Governance Forum (IGF) Leadership Panel?

- In line with the mandate of the IGF and as recommended in the Secretary-General’s Roadmap for Digital Cooperation, the Secretary-General has established the Panel as a strategic, empowered, and multistakeholder body to support and strengthen the IGF.

The Panel will address strategic and urgent issues and highlight Forum discussions and possible follow-up actions, in order to promote greater impact and dissemination of IGF discussions according to its Terms of Reference.

Composition:

- The 10 members of the Panel have been appointed by the Secretary-General following an open call for nominations, and in line with an equitably distributed, multistakeholder configuration of ministerial-level Government representatives, executive-level representatives of the private sector, civil society and the technical community, as well as “at-large” prominent persons in the field of digital policy.

- In addition, the Panel consists of five ex-officio members, including Secretary-General’s Envoy on Technology Amandeep Singh Gill as well as senior representatives of the current, immediately previous, and immediately upcoming IGF host countries.

- They will serve a two-year term during the 2022-23 IGF cycles

Tunis Agenda:

- The IGF is an outcome of the Tunis phase of the World Summit on the Information Society that took place in 2005.

- In the Tunis Agenda, Governments asked the Secretary-General to convene a “new forum for policy dialogue” to discuss issues related to key elements of Internet governance.

- The mandate of the Forum was extended for another 10 years in December 2015, during the high-level meeting of the General Assembly on the overall review of the implementation of the World Summit on the Information Society outcomes.

- The 17th edition of the Forum will take place from November 28 to December 2 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

The Centre vs State tussle over IAS postings

(GS Paper 2, Governance)

Context:

The Government of India (GOI) painfully admitted recently that fewer and fewer All India Services (AIS) officers working in States were coming forward to opt for a tenure with the Centre.

Details:

- An overwhelming majority would like to be in the comfort zone of their State cadres and vegetate there rather than migrate, albeit even for one short spell of three to five years to New Delhi and its neighbourhood to work for the Union Government.

- This is no reflection on the Centre’s ability or willingness to offer incentives to maintain the morale of Indian Administrative Services(IAS) and Indian Police Service (IPS) officers who choose to work for it on deputation.

Positives in working for the GOI:

- These include a psychological satisfaction of contributing to the formulation of national policy on many critical issues, such aseducation, health care or preservation of the environment.

- This throws up manyopportunities for foreign travel and a chance to be deputed to work for international agencies. These prospectsdo not, however,seem to be attractive enough for many officers to crave for a posting in Delhi.

- Several factors account for this reluctance. These include the rigour of the GOI routine, long hours of work and the need for extreme clinicalcare in thepreparation andsubmission of reports going up the hierarchy sometimes up to the Prime Minister himself.

Concerns:

- There are only a few who are fortunate enough to be allotted to their home State or closer. Not surprisingly, many willing to go to Delhi on deputation are those assigned to the Northeastern States.

- Officers shying awayfrom going to Delhi is not a new phenomenon, but is one that has lately assumed grave proportions. This is a serious situation if one reckonsthatthe manpower demands of GOI ministries (at the level of Deputy Secretaries and Directors who generally come from the IAS) are growing.

- There is no doubt now as there is a lateral entry scheme meant for qualified personnel from the public and private sectors. Their number is too small to make even a marginaldifference to the deteriorating vacancy position at the Centre.

Vacancies in Government agencies:

- The case of the Indian Police Service (IPS) is equally bad. There are far too many vacancies in the Central Police Establishment comprising the paramilitary forces such as the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), Border Security Force(BSF) and Central Industrial Security Force (CISF), and investigating agencies like the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) and National Investigation Agency(NIA).

- One organisation particularly affected is the CBI. When this is the case, ironically, the non-IPS direct recruits to the para military forces are permanently at war with the Home Ministry (MHA), demanding a greater share of the jobs in the higher echelons.

- The Cadre rules now in place do not permit such expansion of opportunities for the non-IPS officers. A major grouse of the latter is that none of them can ever rise to head the forces.

- The rationale is that they lack the experience at the grassroots of policing essential to operate in unison with the local civil authorities.

- The AIS structure is unique to India and is too delicate to handle during a crisis. No public administration practitioner or scholarabroad can comprehend its nuances.

The AIS appointments:

- The selection of AIS officers is done through the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC), which holds an annual examination that attracts 3,00,000 to 4,00,000 young aspirants, competing for less than 1,000 positions. The appointing authority for those shortlisted from the written examination, followed by an oral interview, is currently the Central government.

- Appointment officers are allotted to various States, the number of officers depending on each State's requirement. Thereafter, they spend most of their career in those States, intervened by short spells of deputation to the Centre.

- While they are functioning under a State government, disciplinary authority is vested in the former, except that a State cannot impose a major penalty on a delinquent AIS officer for any misconduct.

- Suspension of an officer from the service by a State government will have to be ratified by the Centre before the end of three months. This is meant to be a safeguard against any arbitrary action by a State government.

Conclusion:

- Crass politics triumphing over enlightened public administration has become the order of the day. It is in this context that the Centre's dialogue with the States over amending the AIS rules assumes importance.

- Such amendment would empower the Centre to commandeer the services of any officer serving in the States to work for the former, with or without the concurrence of the State concerned or the consent of the particular officer.

- However, it is debatable whether the States will agree to this change. Intriguing times are, therefore, ahead of all of us who are convinced that we need a stable system of civil services to bolster democratic and responsive public administration in our country.

Indo-U.S. Maritime Partnership is still a work in progress

(GS Paper 2, International Relation)

Context:

- The docking of the USNS Charles Drew, a United States Navy dry cargo ship, for repairs at an Indian facility in Chennai last week, marks an important first in the India-U.S. military relationship.

- Although bilateral strategic ties have advanced considerably over the past decade, reciprocal repair of military vessels was still a milestone that had not been crossed.

With the arrival of Charles Drew at the Larsen and Toubro (L&T) facility at the Kattupalli dockyard, India and the U.S. seem to have moved past a self-imposed restriction.

Functional implication:

- During the bilateral 2+2 dialogue held in April 2022, the two countries agreed to explore the possibilities of using Indian shipyards for the repair and maintenance of ships of the U.S. Military Sealift Command (MSC). After the meeting, the MSC carried out an exhaustive audit of Indian yards, and cleared the facility at Kattupalli for the repair of U.S. military vessels.

- The docking of a U.S. military vessel at an Indian facility has both functional and geopolitical implications.

- Functionally, it signals a more efficient leveraging of the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA), the military logistics agreement India signed with the U.S. in 2017. Thus far, India-U.S. cooperation under the pact had largely been confined to the exchange of fuel and stores during joint exercises and relief operations.

- With the arrival of a U.S. military vessel at an Indian dockyard, the template of logistics cooperation seems to have broadened. There is a good possibility now that India would seek reciprocal access to repair facilities at U.S. bases in Asia and beyond.

- Many in India, meanwhile, are seeing the U.S. ship’s docking as a global endorsement of Indian shipbuilding and ship-repair capabilities.

Boost for ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ and ‘Make-in-India’:

- In recent years, India has sought to showcase its private shipyards, in particular the L&T, which has developed significant ship design and construction capability at its yards in Hazira (Gujarat) and Kattupalli.

- At a time when the Indian Navy has taken delivery of the INS Vikrant , the country’s first indigenously constructed aircraft carrier, the spirits of Indian shipbuilders are already riding high.

- As Indian observers see it, the presence of the USNS Charles Drew in an Indian dockyard is a boost for ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ and ‘Make-in-India’.

The political signal:

- Politically, it signals a consolidation of the India-U.S. partnership, and the Quadrilateral (India, Japan, Australia and the United States) Security Dialogue.

- Despite its intention to strengthen logistics exchanges among Quad members, India has desisted from offering foreign warships access to Indian facilities.

- Notwithstanding the odd refuelling of foreign warships and aircraft in Indian facilities, India’s military establishment has been wary of any moves that would create the impression of an anti-China alliance.

- Yet, Indian decision makers evidently are willing to be more ambitious with the India-U.S. strategic relationship. India’s decision to open up repair facilities for the U.S. military suggests greater Indian readiness to accommodate the maritime interests of India’s Quad partners.

Strategic implications for U.S.

- For U.S, the strategic implications of the docking in India are no less tangible. This is an incremental step forward in the U.S. moving to bolster its military presence in the Eastern Indian Ocean.

- Recent assessments of the evolving security picture in the Indian Ocean point to the possibility of China’s military expansion in the Asian littorals, holding at risk U.S. and European assets.

- Reportedly, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) has been readying to play a more active security role in the region.India’ s offer of repair services for U.S. military vessels could kickstart a process that would culminate in India opening up its naval bases for friendly foreign warships.

- At a time when India has shied away from backing the U.S. position in the Russia-Ukraine war, greater India-U.S. synergy in the Indian Ocean littorals could galvanise the supporters of closer bilateral ties.

- It would revive talk about the bilateral as a defining partnership in the Indian Ocean, and of India’s potential to counter China in the Indian Ocean.

- Coming on the heels of the delivery of the first two U.S. manufactured MH-60R (Multi Role Helicopters) to India, the visit of the USNS Charles Drew has given Indian and U.S. observers much to be optimistic about.

Combined Maritime Forces Cooperation:

- Meanwhile, the Indian Navy has formally commenced its cooperation with the Bahrain-based multilateral partnership, Combined Maritime Forces (CMF), as an ‘associate member’.

- This comes months after India had announced its intention to join the grouping in furtherance of its regional security goals. India’s political and military leadership is seeing this as a demonstration of Indian commitment towards the collective responsibility of ensuring security in the shared commons.

- The India-U.S. relationship is still some way from crossing a critical threshold. For all the hype in the media surrounding India’s membership of the CMF, the modalities of the engagement are still being worked out. The Indian Navy, it seems, has stopped short of formally joining the group, of which the Pakistan Navy is a key member.

- Despite increased engagement with the U.S. Navy, India’s liaison officer at the U.S. Navy component (NAVCENT, or the U.S. Naval Forces Central Command) in the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) is still the military attaché at the Indian Embassy in Bahrain.

Limited in scope now:

- Even with the docking of the U.S. vessel at Kattupalli, Indian analysts ought to recognise that the U.S. military sealift command has no warships.

- The MSC is charged with delivering supplies to U.S. bases, and deals only with transport vessels of the U.S. Navy. The agreement with India for the repair of U.S. military vessels is limited to cargo ships.

- U.S. decision makers are unlikely to seek Indian facilities for repair and replenishment of U.S. destroyers and frigates in the near future until New Delhi is clear about the need for strategic cooperation with the U.S. Navy.

Way Forward:

- By many accounts, then, the India-U.S. maritime relationship remains a work in progress. There has doubtless been some movement ahead, but it is far from clear whether navy-to-navy ties are headed towards a wide-ranging and comprehensive partnership in the Indian Ocean littorals.