What has France ruled on abortion rights? (GS Paper 2, Social Justice)

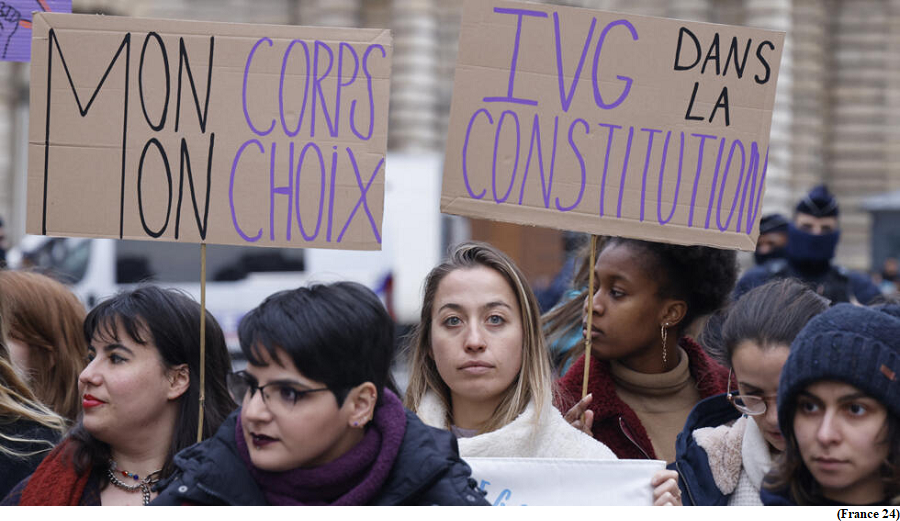

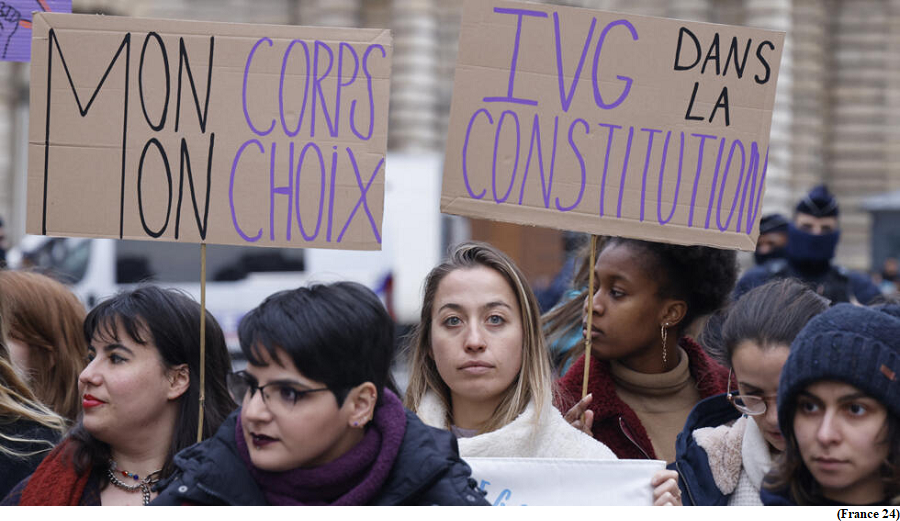

Why in news?

- In a global first, France inscribed the guaranteed right to abortion in its constitution on March 8 sending a powerful message of solidarity with women’s rights on International Women’s Day.

Details:

- Justice Minister Eric Dupond-Moretti used a 19th-century printing press to seal the amendment in France’s constitution at a special public ceremony.

- The move comes after a rollback of abortion rights in the U.S. in recent times, especially the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in 2022 to overturn a 50-year-old ruling in Roe versus Wade.

Background:

- Abortion, although legal in France since 1975, will now be a “guaranteed freedom” for women. Although rare, amending the constitution is not without precedent in France.

- The French constitution has been modified nearly 25 times since it was adopted in 1958.

- The last instance was in 2008 when Parliament was awarded more powers and presidential tenure was limited to a maximum of two consecutive five-year terms in office.

What does the amendment stipulate?

- The Bill amended the 17th paragraph of Article 34 of the French constitution and stipulates that “the law determines the conditions by which is exercised the freedom of women to voluntarily terminate a pregnancy, which is guaranteed.”

- This means that future governments will not be able to drastically modify existing laws which permit termination up to 14 weeks.

First of its kind precedent:

- France is the only country to currently have such a specification about abortion, although former Communist-run Yugoslavia’s 1974 constitution said that “a person is free to decide on having children” and that such a right can only be limited “for the reasons of health protection.”

- After its disintegration in the early 1990s, several Balkan states adopted similar measures without an explicit constitutional guarantee. For instance, Serbia’s constitution in less specific terms states that “everyone has the right to decide on childbirth.”

- However, some argue that abortion was already constitutionally protected following a 2001 ruling in which France’s constitutional council based its approval of abortion on the notion of liberty enshrined in the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man, which is technically a part of the constitution.

What about other European countries?

- Abortion is currently accessible in more than 40 European nations, but some countries are seeing increased efforts to limit access to the procedure.

- In September 2022, Hungary’s far-right government made it obligatory for women to listen to the pulse of the foetus, sometimes called the “foetal heartbeat,” before they can access a safe abortion.

- Poland, which has some of the most stringent abortion laws in Europe, allows termination only in the event of rape, incest or a threat to the mother’s health or life. Restrictions were further tightened in 2020 when the country’s top court ruled that abortions on the grounds of foetal defects were unconstitutional.

- The U.K. permits abortion up to 24 weeks of pregnancy if it is approved by two doctors. Delayed abortions are allowed only if there exists a danger to the mother’s life. However, women who undergo abortions after 24 weeks can be prosecuted under the Offences Against the Person Act, 1861.

- Italy resisted Vatican pressure and legalised abortion in 1978 by allowing women to terminate pregnancies up to 12 weeks or later if their health or life was endangered. However, the law allows medical practitioners to register as “conscientious objectors,” thereby making access to the procedure extremely difficult.

- The French initiative could, however, embolden efforts to add abortion to the European Charter of Fundamental Rights.

What is India’s stance on abortion?

- India implemented the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act in 1971 to allow licensed medical professionals to perform abortions under specific conditions as long as the pregnancy did not exceed 20 weeks. The Act was further amended in 2021 to permit abortions up to 24 weeks for certain cases.

- The opinion of only one registered medical practitioner will be required for the abortion of a foetus up to 20 weeks of gestation.

- If a pregnancy is 20-24 weeks, the right to seek abortion is determined by two registered medical practitioners but only under certain categories of forced pregnancies, including statutory rape in case of minors or sexual assault; women with disabilities; or when there is a change in the marital status of the woman during pregnancy.

- After 24 weeks, the Act requires a State-level medical board to be set up in “approved facilities”, which may “allow or deny termination of pregnancy” only if there is substantial foetal abnormality.

Why India urgently needs a legal framework for genomics

(GS Paper 3, Science and Technology)

Context:

- The last two decades have seen unprecedented advances in genomics. These advancements have come in the background of our ability to sequence, analyse and interpret genomes at an unprecedented scale, along with an emerging and expanding corpus of evidence to act upon the genomic information for healthcare decision making.

- As the costs of sequencing continue to plummet, the next decade is expected to see widespread use of genome sequencing in clinical settings.

- The population-scale genome programmes currently under way in many large and small countries encompassing millions of genomes would form the foundation and fuel this paradigm shift. This throws open unprecedented new opportunities, as well as significant new challenges.

Status in India:

- India has not been too far behind in human genomics, with the announcement of the first genome sequencing in 2009, 1,000 genomes in 2019 and recently concluded 10,000 genomes last week.

- These efforts undoubtedly have contributed to significant insights into diseases in the population, estimates of the prevalence of many conditions, and more importantly serving as baseline data for decision making, apart from its utility in accelerating research.

- Apart from significant impetus in sequencing individuals at scale, to match similar efforts across the world, a well-thought-through legal and policy framework and wider and integral participation of industry is essential to accelerate this in India.

Challenges:

Data protection:

- Data protection is one of the important components that urgently require a legal framework.

- While the Health Ministry Steering committee clearances are required for research collaborations, the Director General of Foreign Trade notification enables samples to cross borders for commercial purposes. This has been widely exploited by large pharma and research organisations abroad to perform research on Indian samples.

- Despite significant established capacity and expertise in India, a significant number of samples from India are sequenced and/or analysed by companies abroad with little oversight and regulation.

Fragmentation of genetic data:

- Another issue is the fragmentation of genetic data, with a number of organisations providing genetic testing services, the data remain in silos. Well, aggregated summary data of these tests and results could provide key evidence for public health decision making.

- For example, summary data of variants and prevalence of variants reported from labs, without personal/ identifiable information could enable rough estimates of population-level prevalence of diseases and enable the development of cheaper genetic tests. Without a framework for collecting summary information, the data remains inaccessible for public health decision-making.

Discrimination:

- Discrimination based on genetic information is indeed a real concern due to the lack of laws preventing it.

- The U.S. formulated the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act in 2008 which prevents discrimination based on genetic information.

Equity and diversity:

- Equity and diversity in genetic data also is a concern that needs to be addressed especially in a diverse country like India, as unregulated market forces could widen the already acute barriers to access to better healthcare, especially for the poor and ethnic minorities.

- Lack of equity could result in less research, less insights/ evidence for clinical decision making and eventually exclusion of such groups from access to the benefits of genomic technologies.

- Ensuring ethical use of the technology is paramount to both advance it and ensure that people benefit from the use, while also being protected from misuse.

- Evidence-based use of genomics and mechanisms to ensure the quality and validity of genomic tests is therefore key.

- In many countries, professional bodies have come forward to be the vanguards, putting together guidelines, policies and frameworks for fair use. Similar efforts supported by legal provisions are needed in India.

Way Forward:

- By emphasising ethical principles and aligning policies with societal needs, human genomics research can realise its full potential in advancing healthcare, improving outcomes, and enhancing the quality of life. With proper oversight, genomic research can revolutionise healthcare, offering personalised treatments, disease prevention strategies, and diagnostic tools.

- India has the potential to be a leader by enabling genomics for the masses, at an unprecedented scale opening up unprecedented opportunities and heralding a better and healthierfuture for its people, but only if it puts the best foot forward.