Integrated urban water management system (IUWM) (GS Paper 2, Governance)

Context:

- With the rapid growth of cities, water demand has exponentially increased. Even as aspirations cause people to migrate to urban areas, water depletion and scarcity remains a huge challenge staring at people’s faces in the near future.

- As water demand exceeds supply in most cities, water management needs to undergo a revolution to ensure most urban areas can be self-sufficient in the future.

Water demand in urban areas:

- Water demand is going to increase even more, with India’s population in urban areas expected to double by 2050. Around 35 per cent of India’s population lived in urban areas as of 2020.

- In urban areas, only 45 per cent of the demand is met using groundwater resources. Apart from this, climate change, pollution and contamination have also added to the burden on water resources.

Water Management Systems in place:

- In India, there are different water management systems based on utilities like sanitation, urban water, stormwater and wastewater that deal with water-related issues in different localities. Since areas and localities define distribution and water allocation, it is often a challenge to find a unified solution.

- With climate change and population growth leading to increased water use, new solutions have to be conceived for better urban water management. More people in different local contexts need to be made aware of the challenges.

- Similarly, there are changes required in institutions like local departments that play a crucial role. It is essential that holistic and systemic solutions are implemented to solve water issues.

Integrated urban water management system for reliable supply:

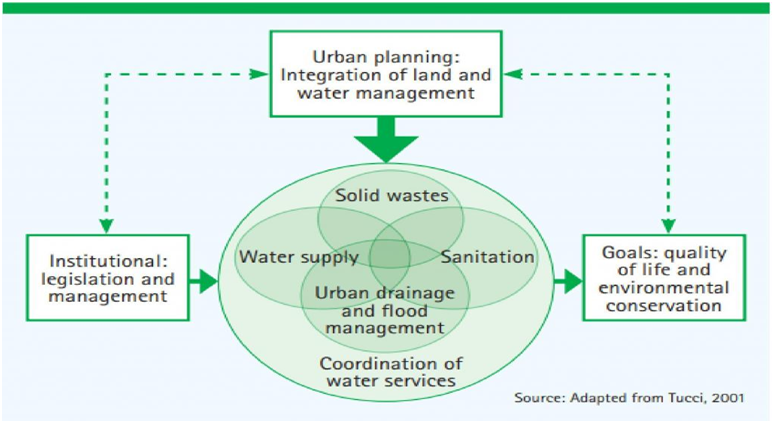

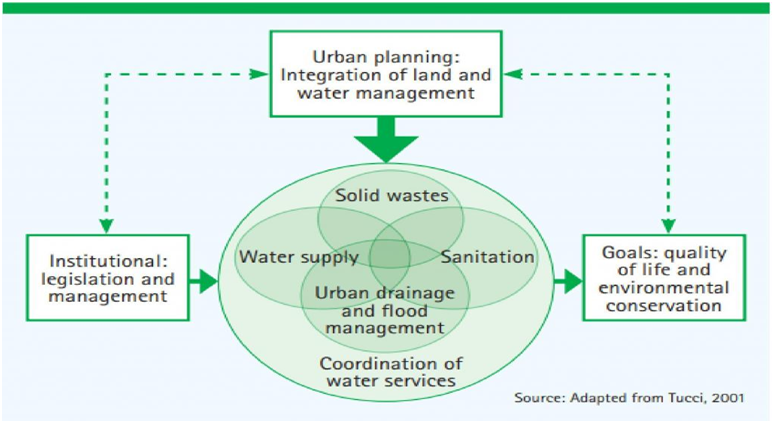

- Integrated urban water management system (IUWM) is a process, which ensures water supply, used water management, sanitation and stormwater management can be planned in line with economic development and land use.

- This holistic process makes coordination among water departments easier at the local level. It also helps cities adapt to climate changes and manage water supply more efficiently.

Approaches to successful urban water management:

- Collaborative action

- Shift in perception of water

- Understanding water as a resource

- Customised solutions for different cities

Collaborative action:

- Collaborative action is one of the leading principles of IUWM. It focuses on a collaborative approach involving all stakeholders. While effective legislation will help guide local authorities, engaging local communities will lead to faster solutions in water management.

- When there is clear coordination between all the stakeholders, it is easier to define priorities, take action, implement changes and take accountability.

Shift in perception:

- The shift in perception must view water in connection with other urban sectors. It is essential to understand how water is inseparable in its connection to economic development, city infrastructure and land use.

- Earlier, many solutions focused solely on seeing water as an independent sector, but now the perception has shifted and it is necessary to view the interdependence with other sectors.

- Once the water situation is gauged, it will be easier for urban local bodies to link a city’s development plans with the water management process.

Understanding water as a resource:

- To understand water as a resource, there is need to realise water is used for different purposes like domestic use, industrial use, freshwater, agricultural use and wastewater.

- This means it cannot be just seen as an end product for consumers but rather as a resource for various end goals. Once all sources are clearly defined, it will be easier to treat different kinds of water based on agricultural, industrial and environmental purposes.

- IUWM ensures water management can be done based on the quality and quantity of water targeted toward specific uses.

Customised solutions for different cities:

- Since IUWM focuses on specific contexts and local requirements, it prioritises a rights-based solution approach over one-size-fits-all approach.

- Conventional methods did not focus on stakeholder engagement, however, IUWM’s integrated system brings in healthy coordination between all stakeholders.

- This helps to build climate resilience among communities and also produces decisions that are more holistic, catering to different industries and communities.

Water for all:

- IUWM prioritises access to water for the most vulnerable communities. This means incorporating a few changes in the entire system.

- Integrated policies can help secure sustainable development and also ensure there is innovation, efficiency and sustainability at every level.

- Institutional practices in large cities will have to be transformed, but a different approach to stakeholder resource management might yield a positive result.

- IUWM has proven to be a successful practice, but budget constraints, inadequate guidance from authorities and lack of awareness have limited the implementation of this solution. However, recent policies by the central government can help pave the way for state-wise planned implementation of IUWM.

Initiatives by the Government:

- The Centre has started initiatives by implementing the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) for inclusive sanitation solutions and Jal Jeevan Mission for ensuring piped water supply.

- The government has also allowed reuse of water based on circular economy principles. No sustainable development goals (SDGs) can be accomplished without running water, therefore, it is imperative that water is managed efficiently.

- This will help India achieve SDGs in health, sanitation, education, livelihood and education.

Way Forward:

- Adopting IUWM will also help tackle water scarcity, address public health risks and make cities climate resilient. It is the one-stop solution to ensure good health and clean water for all.

Challenges before New CDS

(GS Paper 3, Defence)

Context:

- The appointment of Lt General (retired) Anil Chauhan as the Chief of Defence Staff (CDS) is a welcome move.

- It ends a period of intense but needless speculation about the future of the post and whether the government was contemplating on experimenting with a naval or air force officer, or doing away with it altogether.

Civilian supremacy:

- The armed forces in a mature democracy are normally seen as a constitutionally empowered instrument of the state under the umbrella of civilian supremacy. If one draws on the Clausewitzian paradigm of “war is a continuance of policy by other means”, they are also seen as political instruments of the state.

- In his seminal work, ‘The Soldier and the State’, Samuel Huntington spoke about subjective civilian control over a professionalised military, where the latter operates with a great deal of autonomy and is largely trusted by the politicians to offer sound policy advice. This has largely been the model followed in the West with different degrees of control exercised by the political executive.

- In several ways, India’s armed forces have also followed this model with the difference that a powerful layer of bureaucracy has catered to the sporadic interest among politicians in matters related to national security and acted as a policy interface between the two.

Challenges before the new CDS:

- The first challenge for the new CDS is in terms of prioritisation and building a bridge between a government in a hurry and an organisation that is resistant to change, shackled by tradition and plagued by continued turf battles that cannot be wished away.

Competing requirements:

- His next set of challenges will be to balance five competing requirements that have overwhelmed the armed forces in recent years and exposed the shortage of intellectual capital within.

- First, the need to build operational capability at a pace that will ensure that the military power asymmetry vis-à-vis China remains manageable.

- Second, integrating military planning and training to levels that go beyond lip service. There is little doubt that the need to create fresh structures to support integrated training, planning and operations is inevitable. Hard questions will have to be asked about whether India-specific requirements have been adequately addressed in the current structures. There will be no easy answers and individual services will have to walk the extra mile under the reassuring and credible umbrella of the CDS.

- The third requirement is in the area of policy, doctrines and strategy. Armed forces across the world are driven by structured processes, tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs). Policies and doctrines are easier to evolve under the cover of clearly articulated national and military strategies. Though the strategic establishment is divided on the pressing need for a National Security Strategy (NSS), the CDS has his task cut out to link the NSS with transformation and expedite its promulgation.

- His fourth area of focus has to be on balancing the need to retain the operational capability and the government’s push towards self-reliance in defence manufacturing. Considering that this push demands a paradigm shift in the thinking of India’s defence innovation and manufacturing ecosystem, the CDS should ensure that the current silos of innovators and designers (scientists), manufacturers (PSUs and the private sector) and users (armed forces) are broken down.

- Enduring capabilities can be created only if users are afforded lateral entry into the innovation and manufacturing space. One needs to look no further than the US, France and Israel to embrace this push. However, this again links to forcing the armed forces to step out of their comfort zone and develop diverse intellectual capital.

India’s martial traditions:

- The last challenge will be in the realm of shedding several infructuous colonial legacies and traditions and fostering a sense of pride in India’s martial traditions that go back to epics such as the Mahabharata, and to the Maratha and Chola empires.

- Independent India’s armed forces have been adaptable and flexible and should not find it difficult to blend what is good from recent times with what offers value from the past, nowhere else in the world have Soviet-built MiG-21s and MiG-29s adopted Western air combat tactics with such ease.

Way Forward:

- The CDS must not hesitate to speak truth to power. He must be impartial while taking tough decisions and hold national interest above all else, that will be the test of his acumen.

- In a rapidly-evolving geopolitical and global security environment, in which India continues to face challenges across the spectrum of conflict, the CDS has his task cut out.

Supreme Courts abortion ruling

(GS Paper 2, Judiciary)

Why in news?

- Recently, the Supreme Court in a significant judgment said it is unconstitutional to distinguish between married and unmarried women for allowing termination of pregnancy on certain exceptional grounds when the foetus is between 20-24 weeks.

- The decision follows an interim order in July by which the court had allowed a 25-year-old woman to terminate her pregnancy.

- The ruling, incidentally delivered on World Safe Abortion Day (September 28)emphasises female autonomy in accessing abortion.

What is the court’s decision?

- A three-judge Bench comprising Justices D Y Chandrachud, A S Bopanna, and J B Pardiwala framed the interpretation of Rule 3B of the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Rules, 2003, as per which only some categories of women are allowed to seek termination of pregnancy between 20-24 weeks under certain extraordinary circumstances.

- The challenge to the provision was made in July by a 25-year-old unmarried woman who moved the court seeking an abortion after the Delhi High Court declined her plea. The woman’s case was that she wished to terminate her pregnancy as “her partner had refused to marry her at the last stage”.

- She also argued that the continuation of the pregnancy would involve a risk of grave and immense injury to her mental health. However, the law allowed such change in circumstances only for “marital” relationships.

- The Supreme Court, holding that the law had to be given a purposive interpretation, had allowed the petitioner to terminate her pregnancy in an interim order. However, the larger challenge to the law, which would benefit other women as well, was kept pending.

What does the law on abortion say?

- The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act allows termination of pregnancy by a medical practitioner in two stages.

- After a crucial amendment in 2021, for pregnancies up to 20 weeks, termination is allowed under the opinion of one registered medical practitioner.

- For pregnancies between 20-24 weeks, the Rules attached to the law prescribe certain criteria in terms of who can avail termination. It also requires the opinion of two registered medical practitioners in this case.

- For both stages; within 20 weeks and between 20-24 weeks termination is allowed “where any pregnancy is alleged by the pregnant woman to have been caused by rape, the anguish caused by the pregnancy shall be presumed to constitute a grave injury to the mental health of the pregnant woman”.

For pregnancies within 20 weeks, termination can be allowed if:

- the continuance of the pregnancy would involve a risk to the life of the pregnant woman or of grave injury to her physical or mental health; or

- there is a substantial risk that if the child was born, it would suffer from any serious physical or mental abnormality.

Any woman or her partner:

- The explanation to the provision states that termination within 20 weeks is allowed “where any pregnancy occurs as a result of failure of any device or method used by any woman or her partner for the purpose of limiting the number of children or preventing pregnancy, the anguish caused by such pregnancy may be presumed to constitute a grave injury to the mental health of the pregnant woman”.

- The phrase “any woman or her partner” was also introduced in 2021 in place of the earlier “married woman or her husband”.

- By eliminating the word “married woman or her husband” from the scheme of the MTP Act, the legislature intended to clarify the scope of Section 3 and bring pregnancies which occur outside the institution of marriage within the protective umbrella of the law.

Who falls in the category of women allowed to terminate pregnancy between 20-24 weeks?

- For pregnancies between 20-24 weeks, Section 3B of the Rules under the MTP Act lists seven categories of women:

- survivors of sexual assault or rape or incest;

- minors;

- change of marital status during the ongoing pregnancy (widowhood and divorce);

- women with physical disabilities (major disability as per criteria laid down under the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016);

- mentally ill women including mental retardation;

- the foetal malformation that has substantial risk of being incompatible with life or if the child is born it may suffer from such physical or mental abnormalities to be seriously handicapped; and

- women with pregnancy in humanitarian settings or disaster or emergency situations as may be declared by the Government.

What is the court’s interpretation?

- The court stated that the whole Rule 3B(c) cannot be read in isolation but has to be read together with other sub-clauses under 3B. When other sub-clauses do not distinguish between married or unmarried women, for example survivors of sexual assault, minors, etc., only 3B(c) cannot exclude unmarried women.

- Rule 3B(c) is based on the broad recognition of the fact that a change in the marital status of a woman often leads to a change in her material circumstances.

- A change in material circumstance during the ongoing pregnancy may arise when a married woman divorces her husband or when he dies, as recognized by the examples provided in parenthesis in Rule 3B(c).

- The fact that widowhood and divorce are mentioned in brackets at the tail end of Rule 3B(c) does not hinder court’sinterpretation of the rule because they are illustrative.

- The court also expanded on Rule 3B(a) “survivors of sexual assault or rape or incest” to include married women in its ambit. Although it does not have the effect of striking down the marital rape exception under the Indian Penal Code, the ruling said that even women who have suffered “marital assault” can be included under the provision.

What is the effect of the judgment?

- The court’s “purposive interpretation” states that the common thread in Rule 3B is “a change in a woman’s material circumstance”. While the ruling recognises the right of unmarried women, it leaves the enforcement of the right to be decided on a case-to-case basis.

- It is not possible for either the legislature or the courts to list each of the potential events which would qualify as a change of material circumstances. Suffice it to say that each case must be tested against this standard with due regard to the unique facts and circumstances that a pregnant woman finds herself in.

- This means the decision will be in the hands of the registered medical practitioners and if unsatisfied, the woman can approach the court.